Warrants Guidebook

What are Warrants?

Warrants have become increasingly popular because they give investors exposure to an underlying share/index for a fraction of the price. The movements in the warrant price are also usually much greater than the movement in the price of the underlying share/index. This means their potential to deliver a higher percentage return and higher risks is also increased.

Please click on each of the tiles below for more details

-

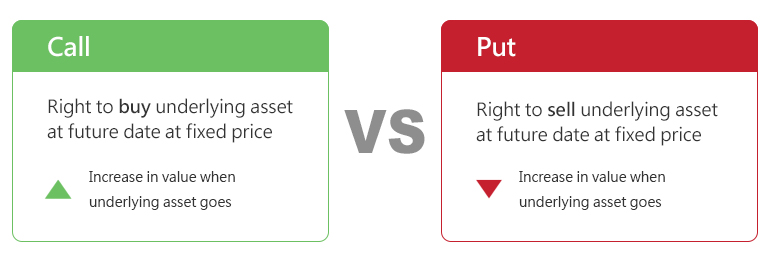

Call vs Put

-

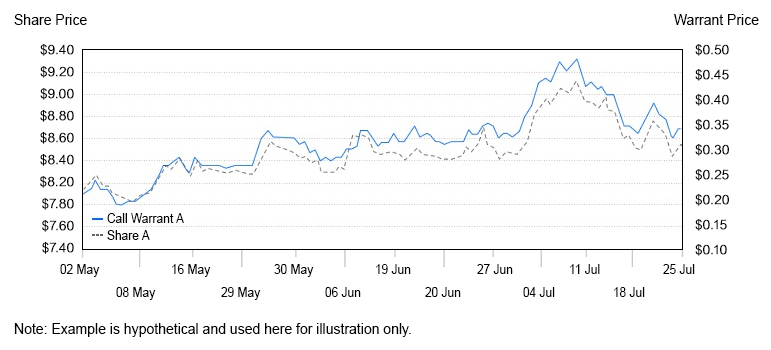

How a Call Warrant works

Here's a look at an example of an investment in a call warrant over Share A. The dotted line here represents the Share A underlying share while the yellow line is the call warrant over Share A. As we can see from the graph, the two lines move in tandem with each other – the call warrant moves up when the Share A underlying share goes up, and likewise follows it downward.

Suppose you have a bullish view on Share A with the share price at $8.40. In this case, instead of paying $8.40 per share for an exposure over Share A, you could buy a call warrant for under $0.20, less than three percent of the share price.

Assuming your view was right and Share A moved to your target price of $9.10, this would translate to a return of 8.3% in 2 months if you had purchased the shares. However, if you bought the call warrant instead of the shares, you would have made a 71.7% return, more than 8 times that of the share price move.

This is an example of gearing at work, and the advantage warrants offer – a greater potential profit (or greater potential loss) as a percentage of your invested capital.

Share A Call Warrant A 6 May $8.40 $0.230 11 July $9.18 $0.395 Profit +9.3% +71.7% Note: Example is hypothetical and used here for illustration only. -

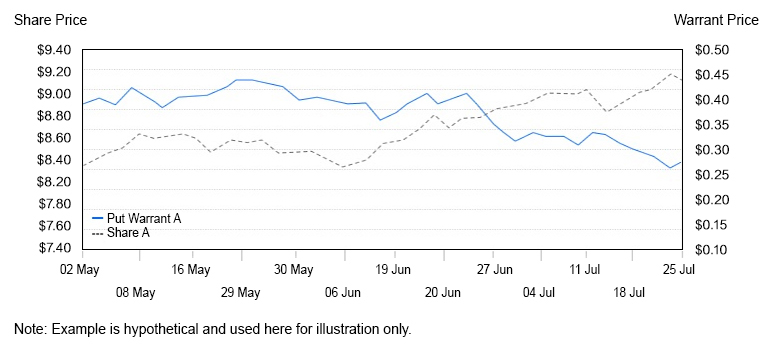

How a Put Warrant works

If you want to profit from downward movements or are fearful of losses on your existing portfolio from short-term corrections, put warrants may be the instrument you are looking for.

In our example below using a put warrant over Share A, you can see that the put warrant, denoted by the yellow line, moves in inverse directions with the Share A which is denoted by the dotted line.

If you have a view that the Share A had moved too high within a short space of time and due to fall, you could purchase a put warrant on Share A to profit from your view.

In our example, the Share A took a 10.9% tumble over one month. If you had purchased the put warrant at $0.23 when the underlying share was at $9.20, you could then sell the put warrant at $0.42 when the share was traded at $8.20, earning a profit of 82.6%.

If you were holding Share A, the 82.6% gain from the put warrant could be used to offset the losses you had on your shares. This strategy is known as “hedging”.

Share A Put Warrant A 11 July $9.20 $0.23 11 August $8.20 $0.42 Profit/Loss -10.9% +82.6% Note: Example is hypothetical and used here for illustration only. -

How are Warrants named

Like shares, warrants are listed on the Hong Kong Exchange and can be bought and sold through any stockbroker. The name of a warrant is basically made up of different figures and English letters, and there are five pieces of basic information, take AB-CDEF@EC1101 as an example:

AB ----- The issuer

CDEF ----- The underlying asset: CDEF Company

@ ----- Cash settlement on expiry date. *represents a spot settlement (but there is no warrant with spot settlement in the current market)

E ----- A European style warrant, which can only be exercised on the expiry date; A represents an American style warrant (but there is no American style warrant in the current market); X represents a non-standard warrant

C ----- Represents a Call warrant; P represents a Put warrant

1701 ----- Represents that the expiry date is January of 2017The English letters at the end of the name means an issuer has issued more than one warrant with the same underlying asset and expiry year and month. The issuer then add the letters A, B, C, D, E, etc. to distinguish and avoid confusion.